Anti-German Sentiment in Iowa

| Grade | 9th -12th Grades | Class | U.S. History | Length of Lesson | 50 Minutes |

| Lesson Title | Anti-German Sentiment in Iowa |

| Unit Title | Homefront During WWI |

| Unit Compelling Question | Was America justified with Anti-German sentiment? |

| Historical Context: Anti-German Sentiment in WW I Through the last half of the 19th C., Germany provided more immigrants to Iowa than any other enthic group. They often settled together in cities, towns, or rural neighborhoods and preserved many aspects of their traditional culture. German was the language in the home, in the school, in church, and in many business connections. German language newspapers covered local, national, and international events of interest to their readers. While Germans often formed a majority along many of the larger Mississippi River cities like Dubuque and Davenport and in western Iowa towns like Carroll and Audubon, they were a visible presence in many communities across the state. In some significant ways, some aspects of German culture clashed with beliefs and customs of native-born culture. Many Germans were Catholic in a state dominated by Protestants. Germans also observed a "continental Sunday" socializing with friends and attending outdoor concerts or other entertainments in the afternoon and evening. In the greatest tension of all, Germans opposed Protestant efforts to restrict the sale of alcohol. Beer was an accepted part of German culture while many Protestants saw the beer hall as a threat to the sanctity of the human and public safety. When WWI started in 1914, Americans were divided in their support of the competing sides. Immigrants nearly always favored their homelands. Resenting centuries of British domination, many of the Irish spoke out against the French-English alliance. Germans naturally pointed to British attempts to stifle German development. Similarly, Canadians, British and French immigrants favored their native lands. The dominant feeling, however, was that the war was a European conflict. Its issues did not concern the United States and America must do what it must to avoid being dragged in. However, with German attacks on American shipping and then all-out submarine warfare, the United States declared war on Germany and entered the conflict on the side of the Allies. With the help of a very effective propaganda office directed from the highest levels in Washington, D.C., public opinion immediately shifted against Germany: its leaders, its army, and all things German. Iowa followed the trend. Local committees organized to root out any evidence of subversive activities. German-Americans were subject to pressures to prove their support for the United States' war effort. If they did not buy war bonds or donate to the Red Cross, local citizens' groups might visit their homes to make them sign a pledge. Any comment in support of Germany drew threats of violence or ostracism from the community. Sometimes German-Americans experienced minor incidents of violence. German symbols were targets. German language classes in schools were dropped. German books were taken off the shelves and sometimes burned. Businesses with German names adopted American identities. Even German foods came in for Americanization: sauerkraut became Liberty Cabbage. Iowa claimed the national spotlight when Governor William Harding issued what became known as the Babel Proclamation in May, 1918. He declared that it was illegal to speak any language but English in public. That included church and telephone conversations. Ethnics other than German also found themselves caught up in the law. Iowa contained many ethnic communities. Danes, Dutch, and Norwegians protested when they could no longer hold church services in their own language. The governor's proclamation was on shaky legal grounds, and it drew derision from within Iowa and across the nation. However, its impact on public opinion further strengthened anti-German sentiment. Anti-German sentiment undercut ethnic communities after the war as well. Any visible attachment to a former homeland could risk one charges of being less the "100% American". Before the war, Iowa was dotted with a variety of strong ethnic communities. Improvements in transportation, especially the automobile, accelerated the integration of local populations. National prohibition was adopted in 1919 with passage of the 21st Amendment making the manufacture and sale of most forms of alcohol illegal. Because beer was such a staple of German culture, many rural German communities continued to manufacture bootleg liquor and make themselves targets of law-enforcement agencies, further drawing the ire of prohibition advocates. |

|

| Lesson Supporting Question | |

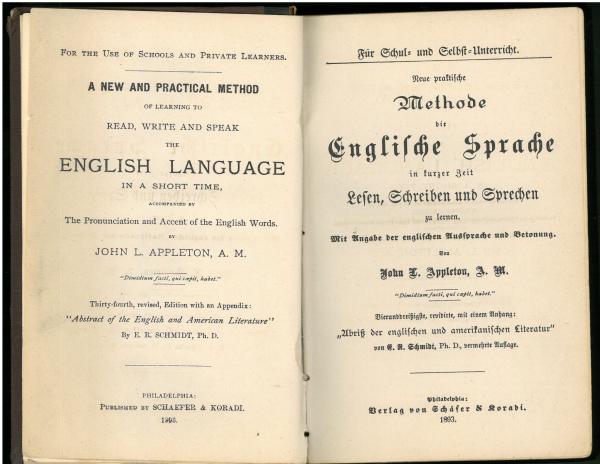

| Lesson Overview | Students will be shown an image of a textbook that was used to teach Germans to speak English during WWI and answer questions regarding the primary document. This lesson goes into depth on Anti-German sentiment in Iowa during WWI. This lesson will review the Babel Proclamation and the events that had transpired as a result of this including the textbook mentioned before. Students will read articles and have group discussions over these events and end the day answering some questions for an exit ticket. |

| Primary Sources Used |

|

| Resources Needed | https://medium.com/iowa-history/while-the-u-s-fought-germans-in-europe-iowa-fought-their-language-at-home-7a444abd3846 https://medium.com/iowa-history/when-sauerkraut-became-liberty-cabbage-bb84f4369d52 |

| Standard | |

| Lesson Target | Students will be able to understand how primary text and documents are interrupted to the public.;Students will be able to understand how a certain event can cause a ripple effect causing other events to happen. |

| Lesson Themes | Immigrants, World War I |

|

| Formative Assessment (How will you use the formative assessments to monitor and inform instruction?) |

Students will be assessed based on their group's discussion answers and how they relate to Anti-German sentiment in Iowa. They will also be assessed through their responses to the exit ticket by examining if they can connect why Iowan's would do this and how events can cause a ripple effect in history. |

| Summative Assessment (How does the lesson connect to planned summative assessment(s)?) |

| Author | Austin Bowman | Created | Last Edited | ||||

| Reviewer: Chad Christopher, History Education, University of Northern Iowa | |||||||

| Lesson Plan Development Notes: Teaching Methods, University of Northern Iowa, Spring 2019 | |||||||