The Iowa Pacifist: Conflict in the Homefront

| Grade | 9th -12th Grades | Class | U.S. History | Length of Lesson | 50 Minutes |

| Lesson Title | The Iowa Pacifist: Conflict in the Homefront |

| Unit Title | Homefront During WWI |

| Unit Compelling Question | Who all are affected by world war? |

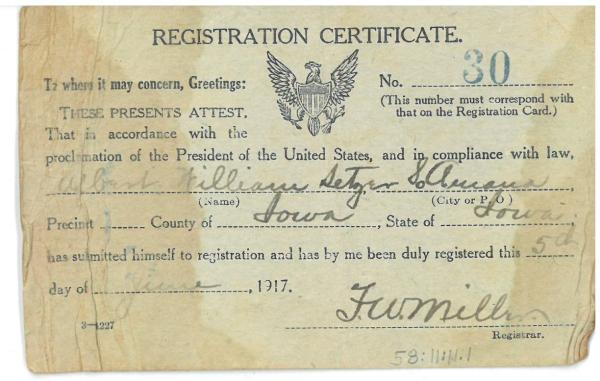

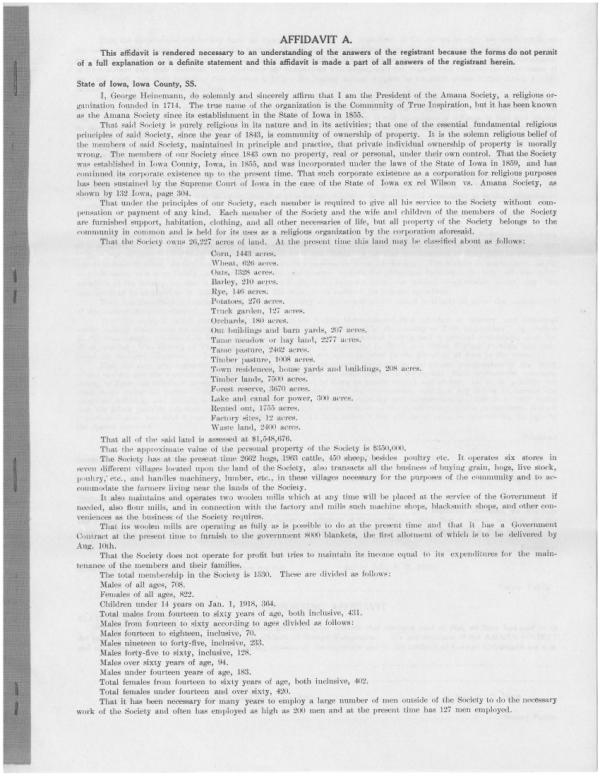

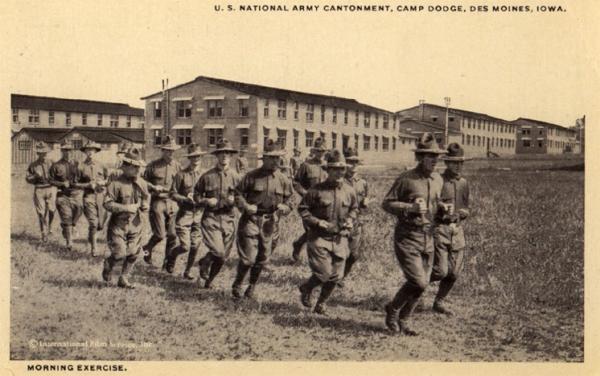

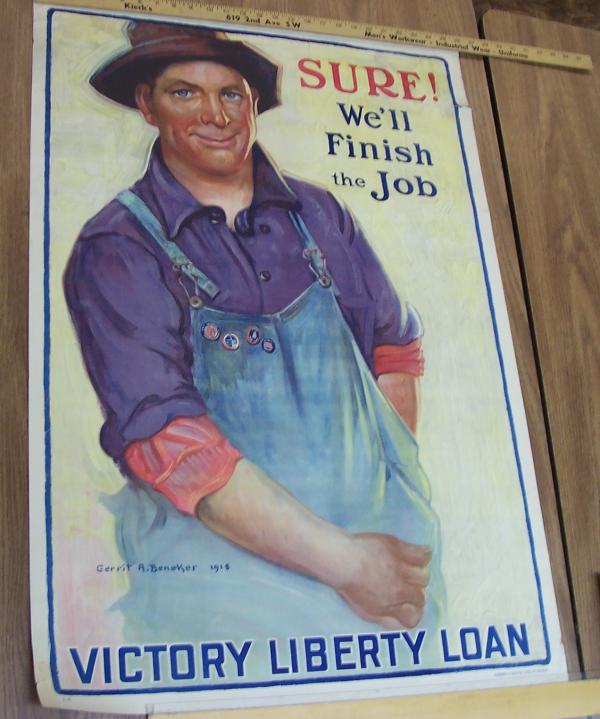

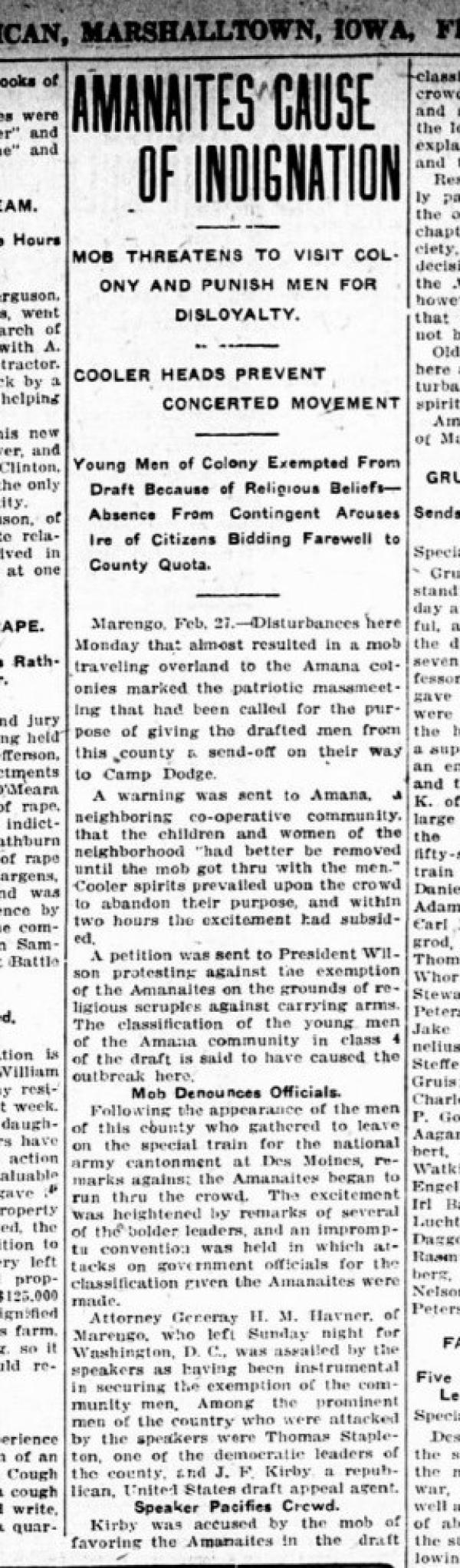

| Historical Context: 2018.002.002 Victory Liberty Loans were a type of war bond that was sold during World War I. Buying these loans was seen as a sign of patriotism. During the first Liberty Bond campaign of 1917, Iowan counties would receive a quota and residents were expected to pay the minimum amount. Due to little advertisement and interest, many counties did not reach their quota, resulting in a reputation of being unpatriotic. With the following campaigns, methods to pressure Iowans were enacted such as setting up "Loyalty Courts" in cities such as in Linn and Johnson County. Those who failed to contribute to the war effort were then required to appear in court. Along with increased advertisement such as posters, the following campaigns were successful. 2018.040.008 2018.040.009 2018.040.018 The members of Amana believed strongly in pacifist views, where they stayed out of European affairs before immigrating to the United States and continued after settling in New York and Iowa. Amana was excused from fighting during the Spanish American and Civil War by paying commutation fees to support Iowan soldiers in their place. The pacifist belief was met with disagreement by Iowa County residents as Amana men were sent home from Marengo in July of 1917 after being originally chosen for the draft in WWI. In January of 1918, the classification status of Amana residents was changed from 1 to 4, mean that they were deferred from fighting. Their place would be taken by other Iowa County men. Believing this was an act of disloyalty, angry Marengo residents marched to South Amana in protest, however the mob was stopped one mile outside of South Amana. After WWI, the exemption of Amana residents from being drafted was rescinded. Despite their pacifist beliefs, the colonies supported the troops by donating to the Red Cross, using Liberty Bonds and War Savings Stamps. The Amana Woolen Mill also produced 35,000 blankets for troops. In total, Amana gave approximately $2,000 per resident to the war effort. 2018.043.001 After the United States entered World War I in 1917, Camp Dodge played a significant role in the expansion of the United States military. Between September 5, 1917 and December 15, 1918, 111,462 recruits, including 37,111 Iowans, trained for service at Camp Dodge. The camp contained 1,409 buildings, twenty miles of streets, 8,000 horses and mules, a power plant, a hospital, and a peak garrison of 46,491 soldiers in July 1918. After the war ended, Camp Dodge became a demobilization center, and over 208,000 soldiers were discharged at the camp. Camp Dodge was established in 1909 under Major General Grenville M. Dodge from Council Bluffs, Iowa who had served as Iowa's strongest commader during the Civil War. On June 15, 1917, the camp was chosen by the US Army Selectional Board as one of 16 regional training camps for the U.S. Army. The camp began to train soldiers from Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota. From July to November 1917, 30 barracks (each held 150 men) were constructed including a mess hall, assembly hall, post office, two headquarters buildings, an auditorium, a hospital, three fire station, libraries and eight YWCA halls. After the war, Camp Dodge only housed Iowa National Guard soldiers. In 1921, the majority of the camp was sold to the Northwest Lumber and Wrecking Company in Minneapolis. The company bought 1,200 buildings for $251,000 and seven miles of the camp was demolished. Since the war, the Camp has served as the Iowa National Guard headquarters and in the 1990s, the addition of the United States Army's National Maintenance Training Center was built to continue the training of state soldiers. |

|

| Lesson Supporting Question | |

| Lesson Overview | The students will have just completed a lesson over the causes of World War I. Along with this lesson, they learned some of the basic political history and diplomatic ties that included everyone in the war. Now, however, we are going to look at a case involving one of the most important aspects of any war - the homefront.

Students will examine the political cartoon and image of soldiers running to connect it to the greater propaganda themes that developed in World War I. After that, students will review a declaration by the Amana Colonies along with the military record of the soldiers from the Amana colonies and discuss if people who choose to not fight in the war can still be patriotic.

|

| Primary Sources Used |

|

| Resources Needed | https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Yf5nVq_Ak2Qo4jqfOJLlFuFLJc5IA-X9_HoOLd3GUdc/edit https://docs.google.com/document/d/1I42ALDv381usVnTWONWaD3o98xyhZg81cCl8jn4WwlM/edit?copiedFromTrash

|

| Standard | |

| Lesson Target | Students will analyze various images and interpret their message;Students will construct an argument around the relationship between pacifism and patriotism. |

| Lesson Themes | Cultural Events, Communal Groups, World War I |

|

| Formative Assessment (How will you use the formative assessments to monitor and inform instruction?) |

Students will do a take-home essay discussing patriotism. In the first part, they will discuss what patriotism means to them and if they believe they’re a patriot and why? In the second part, they are to discuss whether they believe the men from the Amana colonies were patriots? How does the role of religion play in all this? Why would people become so angry with them? |

| Summative Assessment (How does the lesson connect to planned summative assessment(s)?) |

| Author | Zach Steger | Created | Last Edited | ||||

| Reviewer: Chad Christopher, History Education, University of Northern Iowa | |||||||

| Lesson Plan Development Notes: Teaching Methods, University of Northern Iowa, Fall 2019 | |||||||